Eastern European countries are embracing the millions of Ukrainians fleeing Russia’s invasion as a potential workforce but analysts warn it be challenging to integrate them all.

Some 2.5 million people have already fled Ukraine, according to the United Nations, which calls it Europe’s fastest-growing refugee crisis since World War II.

More than half are now in Poland but tens of thousands are also staying in Moldova and Bulgaria, which have some of the fastest shrinking populations.

“Those who are now arriving in the territory of the EU are well-qualified and meet the demand for labour,” said Sieglinde Rosenberger of the University of Vienna, though she warned the welcoming attitude could change.

Other experts asked how eastern European countries, which have a lower GDP than their western counterparts, can handle a huge influx.

Acutely aware of the burden, some countries have already called for more assistance.

– ‘Intelligent, educated’ –

In a letter to the government, the association of Bulgarian employers’ organisations said they could employ up to 200,000 Ukrainians.

They said those who were of Bulgarian origin and able to speak the language would be particularly welcome.

Meanwhile, IT, textile, construction and tourism sector representatives also said they were keen to hire tens of thousands of people.

Bulgaria’s population has dwindled from almost nine million at the fall of communism to 6.5 million now, owing in part to emigration.

The welcome comes from the highest levels.

Bulgarian Prime Minister Kiril Petkov described Ukrainian refugees as “intelligent, educated… highly qualified.”

“These are people who are Europeans, so we and all other countries are ready to accept them,” he said.

Some 20,000 Ukrainians are currently in Bulgaria — the EU’s poorest member — though their numbers are expected to rise if Russia seizes Odessa on the Black Sea.

Hungary — which touts its restrictive migration policy but also struggles with a labour shortage — has also welcomed Ukrainians.

“We are able to spot the difference: who is a migrant, they are coming from the South… and who is a refugee,” nationalist premier Viktor Orban said.

“Refugees can get all the help,” he said last week.

Whether Ukrainians will stay is another question as many arriving move on to elsewhere in Europe where they may have relatives or better prospects.

– Integration issues –

But countries where a large number of refugees end up staying, such as Poland, could become overburdened since many are children and elderly — thus unable to work.

“How will these large numbers be integrated across Europe? This is going to be a problem,” Brad Blitz of the University College London told AFP.

The “breaking point” was yet to come, he added.

Moldova, wedged between Ukraine and Romania with a population of 2.6 million people, has called for urgent help with about 100,000 refugees.

“We will need assistance to deal with this influx, and we need this quickly,” Moldovan Prime Minister Natalia Gavrilita told visiting US Secretary of State Antony Blinken last weekend.

Gerald Knaus of the think tank European Stability Initiative said the EU should prepare now to move hundreds of thousands of people within the bloc.

“It will not work with strict quotas. It will rely on bottom up political support and political leaders saying, ‘We step forward,'” he told AFP.

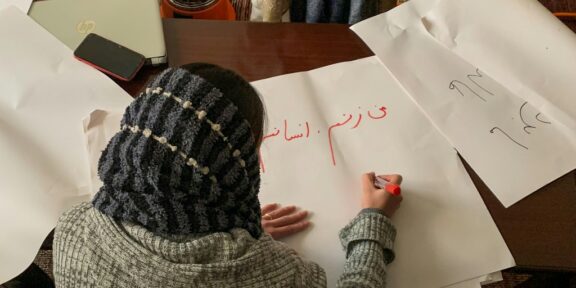

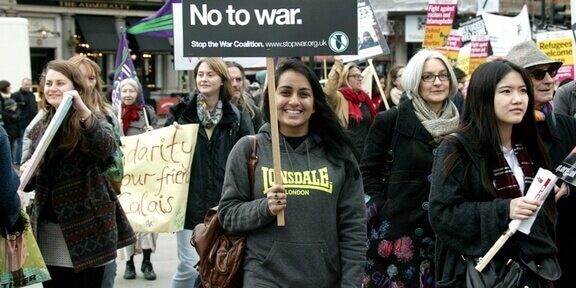

He said the crisis, however, could turn “into one of the great moments of bringing Europeans together around a humanitarian cause”.

The University of Vienna’s Rosenberger said governments that sought to restrict migration had now quickly changed their stance in the face of public sympathy with Ukraine.

But that welcome might not last forever when “in a few months, poorer and less qualified people are expected to come,” she said.