by Katy LEE

Cryptocurrency investors have been transfixed over the past few days by the antics of a mysterious hacker who stole more than $600 million — before giving some of it back.

But is the thief a good samaritan who stole the money to expose a dangerous security flaw, or did they simply realise they were about to be caught?

The hacker struck Poly Network, a company that handles cryptocurrency transfers, on Tuesday in one of the biggest thefts of digital monies in history.

By Thursday they had returned some $342 million — still far short of the total, but enough to raise furious speculation over their motives.

In messages embedded in the transactions, the thief insisted they stole with good intentions.

“I am not very interested in money!” they wrote, adding it was “always the plan” to return the stolen funds.

– Digital sleuths –

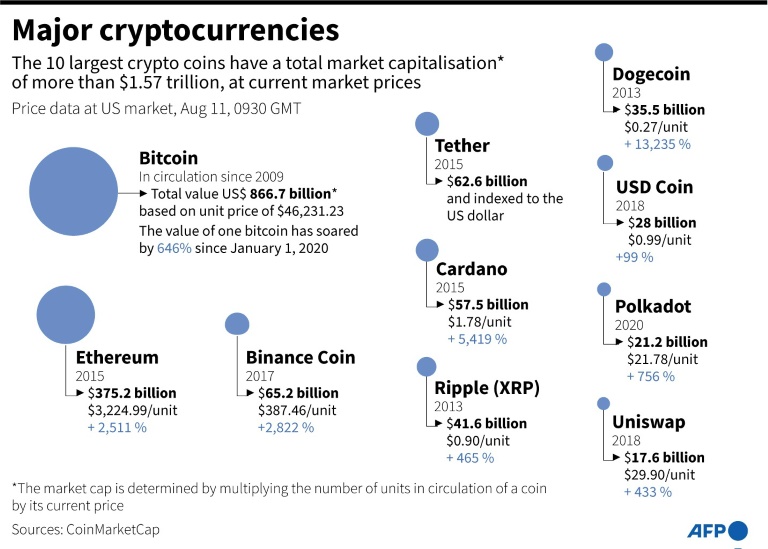

Despite their volatility and concerns over the huge waste of electricity they generate, cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum have soared in popularity in recent years.

Their combined market value currently stands at nearly $2 trillion, creating alluring prospects for hackers.

Most notoriously, thieves stole 850,000 Bitcoins from Japanese exchange Mt. Gox in 2014. Worth around $470 million at the time, the coins would today be worth a staggering $38 billion.

Another Japanese exchange, Coincheck, was hacked for nearly $500 million in 2018.

But in both cases, the technology that cryptocurrency uses allowed some of the funds to be traced — even though for Mt. Gox, it came too late to save the company.

Cryptocurrencies use blockchains, digital ledgers that record every transaction made.

Pawel Aleksander, an expert in tracking stolen cryptocurrency, said thieves typically try to cover their tracks by splitting the money up and moving it around — “sometimes using hundreds of thousands of consecutive transactions”.

But his company Coinfirm is among a growing number that specialise in following dizzyingly complicated blockchain transactions, helping law enforcement agencies and investors to trace stolen assets.

While some crypto-aficionados are hailing the Poly hacker as a hero, others suspect they began handing the money back because sleuths were on their trail.

The returns began after SlowMist, another investigative firm, claimed to have identified some of the hacker’s personal details, including their email.

“It’s hard to say what the hacker’s initial intention was,” said Aleksander’s colleague Roman Bieda.

“The hacker could be simply afraid of action taken against him,” he suggested, although he added that “white hat” ethical hackers do often seek to publicly shame companies for their security flaws.

Some investors would also consider it a “fair bargain” for the hacker to keep some of the money, as a reward for finding the security flaw, Bieda said.

– End of the Wild West? –

Crimes involving cryptocurrencies are on a downward trend, despite spectacular thefts like this one and concerns about their use by criminal gangs.

A report this month by security firm CipherTrace estimated global crypto-crime losses at $1.9 billion last year, down from $4.5 billion in 2019.

It did, however, warn of an alarming rise in hacking and fraud linked to decentralised finance, or “defi” — a form of crypto-financing, including loans, designed to cut out intermediaries like banks.

The Poly heist is part of that trend, with the company calling it the biggest hack “in defi history”.

“The imagination of fraudsters in this industry is constantly developing,” said Syedur Rahman, a British lawyer who specialises in cases involving cryptocurrencies.

But he added that tighter regulations are increasingly forcing cryptocurrency exchanges to verify users’ identities, while law enforcement agencies are growing more experienced in handling crypto-crimes.

Hackers extracted a $4.4 million ransom in Bitcoin from oil company Colonial Pipeline in May, but the FBI was able to track down most of the coins and seize them.

Retrieving stolen crypto-assets can still be difficult, however.

“Criminal activities in crypto are very much multinational,” said Aleksander.

“It’s typical that the victims sit in different jurisdictions, and the exchanges are registered in different jurisdictions.”

Victims’ battle to claw back money stolen in the Mt. Gox hack has been bogged down in years of international litigation.

And hiring sleuths to trace stolen assets is an expensive option that is often out of reach for individual investors hit by hackers.

“When you have a consumer who has lost a nominal sum, there’s not much that can be done,” said Rahman.

kjl/lth

© Agence France-Presse