Troubled Credit Suisse has two days to reassure before the markets open Monday with the spectre of a new turbulent week in global finance looming.

The Zurich-based lender was holding crisis talks this weekend and urgent meetings with Swiss banking and regulatory authorities.

Switzerland’s largest bank, UBS, was reported to be negotiating to buy all or part of Credit Suisse, with the blessing of the Swiss regulatory authorities, according to the Financial Times.

The Swiss National Bank (SNB) “wants the lenders to agree on a simple and straightforward solution before markets open on Monday”, the source said, while acknowledging there was “no guarantee” of a deal.

US asset management giant BlackRock was also reported to be eyeing a move for the troubled bank, but the New York-based company strongly denied this to AFP.

“BlackRock is not participating in any plans to acquire all or any part of Credit Suisse, and has no interest in doing so,” a spokesperson told AFP.

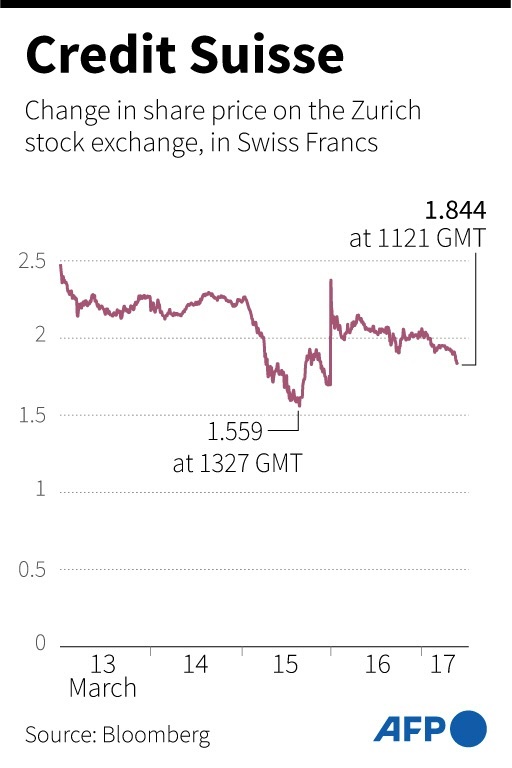

After a turbulent week on the stock market which forced the SNB to step in with a $53.7 billion lifeline, Credit Suisse was worth just over $8.7 billion on Friday evening.

But an acquisition of this size is dauntingly complex.

While Swiss financial watchdog FINMA and the SNB have said that Credit Suisse “meets the capital and liquidity requirements imposed on systemically important banks”, mistrust remains.

– ‘Serious breaches’ –

Credit Suisse has been scandal-plagued for the past two years with its own management admitting “material weaknesses” in their “internal control over financial reporting”.

FINMA accused the bank of having “seriously breached its supervisory obligations” in its relationship with the disgraced financier Lex Greensill and his companies.

In 2022, the bank suffered a net loss of $7.9 billion, against the backdrop of massive withdrawals of money from its customers. It still expects a “substantial” pre-tax loss this year.

“This is a bank that never seems to get its house in order,” IG analyst Chris Beauchamp commented in a market note this week.

Yet more drastic restructuring, closing its investment banking arm or even a takeover by a rival were being mooted by analysts studying Switzerland’s second-biggest bank, one of 30 deemed of global importance to the international banking system.

Amid fears of contagion after the collapse of two banks in the United States, on Wednesday Credit Suisse’s biggest shareholder said it would “absolutely not” up its stake in the bank for regulatory reasons.

The central bank lifeline raises questions about whether an orderly bankruptcy could happen, in which regulators would take over Credit Suisse and take charge of dismantling it.

Credit Suisse’s CET1 ratio, which compares a bank’s capital to its risk-weighted assets, stood at 14.1 percent at the end of 2022 — slightly less than HSBC but more than that of BNP Paribas, which are among the largest banks in Europe.

It now has a huge amount of liquidity on its hands thanks to the SNB’s intervention.

– Merger with UBS –

Analysts at financial services giant JPMorgan, insisting that “status quo is no longer an option”, considered the scenario of a takeover by another bank, with UBS “the most likely”.

The idea of Switzerland’s biggest banks joining forces regularly resurfaces, but is generally dismissed due to competition issues and risks to the Swiss financial system’s stability, given the size of the bank that would be created by such a merger.

“The question arises because there are many candidates which might be interested,” said David Benamou, chief investment officer of Paris-based Axiom Alternative Investments.

“However, the Credit Suisse management, even if forced to do so by the authorities, would only choose (this option) if they have no other solution,” he said.

The bank is starting to roll out its restructuring plan laid out in October, while UBS has spent several years addressing its own issues.

Following the bank collapses in the United States, Credit Suisse’s credit default swaps shot up.

With the SNB’s help, Credit Suisse gained “precious time” to do a more radical revamp, Morningstar analyst Johann Scholtz said.

He believes the current restructuring is “too complex” and “does not go far enough” to reassure funders, clients and shareholders.